The Hub-spokes model

The Hub-spokes model

The Millenium Development Goals (MDG), set by the United Nations in 2000, put emphasis on reducing maternal mortality worldwide by 2015.

The Millenium Development Goals (MDG), set by the United Nations in 2000, put emphasis on reducing maternal mortality worldwide by 2015.

The Millenium Development Goals (MDG), set by the United Nations in 2000, put emphasis on reducing maternal mortality worldwide by 2015. During this MDG era, maternal mortality ratio (MMR) declined in Bangladesh. However, despite this initial progress, MMR remained stagnant between 2010 and 2016, with the recorded 196 per 100,000 live births in 2016 being almost identical to 2010 levels. Unfortunately, Bangladesh continues to have one of the highest maternal and neonatal mortality rates in the world. In recognition of this burden, Bangladesh has adopted the Global Strategy, and is committed to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets. This involves reducing MMR to as low as 70 per 100,000 live births and the neonatal mortality rate to 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030 (from 28 per 1,000 live births in 2014). In order to achieve these ambitious SDG targets, Bangladesh will have to significantly accelerate the rate of reduction of maternal and newborn deaths from that which was observed during the MDG era.

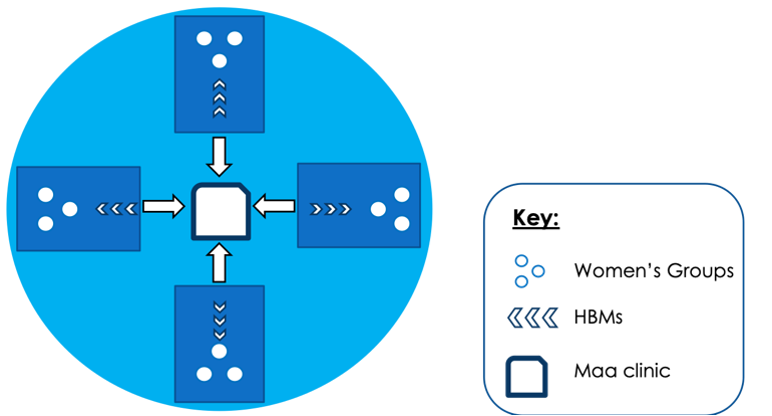

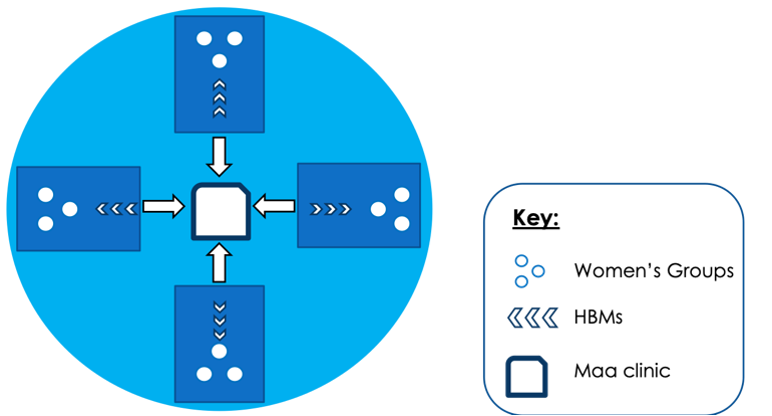

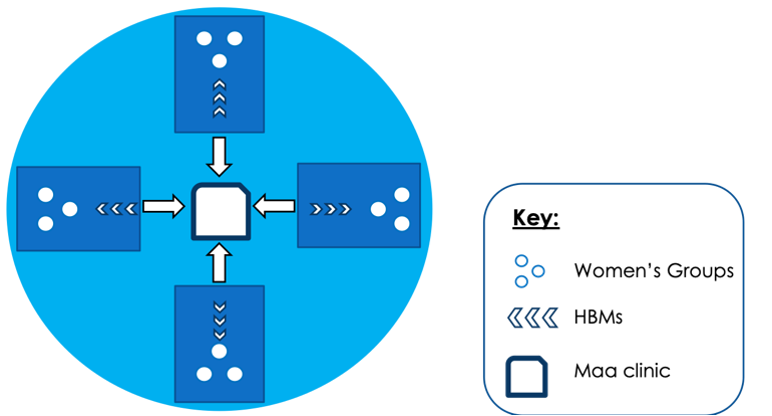

The Maternal Aid Association (Maa) has devised a primary healthcare model to revolutionise maternal healthcare in rural Bangladesh. This is known as the Hub-spokes (HS) model. The HS model has been designed to educate a population, specialise the workforce and connect a fragmented health system. The main aims are to access the remote and resource-poor populations and provide them with integrated and efficient care, and add practical innovation and much needed, targeted resources to the field. It is the blueprint to a model that we hope can be replicated throughout the developing world, in similar resource-poor and remote settings.

The model has a central ‘Hub’, which is the Maa clinic, where Maa specialised doctors will identify and manage high-risk pregnancy cases. The two aspects of community intervention in the HS model are the presence of Health Brigade Members (HBMs) and Women’s Groups (WGs). HBMs are fifth year medical students who will provide antenatal care (ANC) in the homes of mothers. They will also collect data on maternal and neonatal health outcomes, as well as demographic information for future research by Maa. They will be responsible for referring high risk mothers to the Maa clinic for review by the doctors, who will then be responsible for the management of red-flag symptoms (such as high blood pressure) and for rapid referral to a local government hospital in cases of emergency. Further, WGs are an example of community interventions. Local women from the community meet regularly to discuss issues of concern with their facilitator. WGs in Bangladesh have previously been shown to be successful in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, thus Maa has employed them as a strategy to educate and empower women. The chosen location for the HS model pilot study is Moulvibazaar.

There are three main aspects of the model

Figure 1: The Hub-Spokes Model. There are three main aspects to the model: Women’s Groups, Health Brigade Members, and the MAA Clinic with its specialised doctors. The MaaConnect app will be used to bridge the technological gap between the different components of this model.

We have several key stakeholders in each component of the HS model. The Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists (RCOG) in Bangladesh and the UK are involved in training the Maa specialised doctors. Professor Kishwar Azad (UCL) is a Maa academic advisor who will be responsible for starting the WGs intervention in our villages and Dr. Ed Fottrell (UCL) is our academic advisor responsible for overseeing the entire project, particularly from a research perspective. Finally, Maa has affiliations with five medical schools in Sylhet, from which third and fourth year medical students will be sent to act as HBMs in the community.

Maa will conduct the HS model pilot in Moulvibazaar, Bangladesh. Moulvibazaar is a South Eastern district in Sylhet, composed of seven sub-districts or upazilas: Moulvibazaar Sadar, Barlekha, Juri, Srimangal, Kulaora, Rajnagar and Kamalganj. The total population count for this district is 1.9 million and the population is 690 people/km2 (BBS, 2013). This is extremely high and suggests that there must be a large population living in overcrowded households. The majority of the Moulvibazaari population are Bengali, however there are a few indigenous tribes, such as the Manipuri and Khashia tribes, who do not speak Bengali. The literacy rate in Moulvibazaar is 51%. Unfortunately, an estimated 500,000 people in Moulvibazaar live under the poverty line, with another 18% living in extreme poverty.

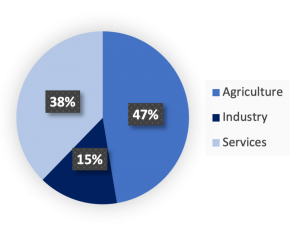

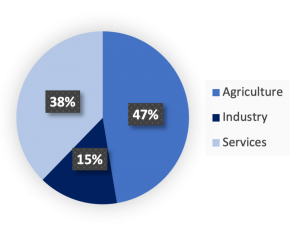

The main source of income for families is through agricultural activities (Figure 2) and the region is very well known for its tea gardens.

Figure 2: Employment structure of Moulvibazaar. Adapted from Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2011).

Globally, it is estimated that 75% of women have access to routine healthcare facilities, but only 25% can access emergency care during the peripartum period. Moulvibazaar is the chosen village for the HS pilot study due to a number of reasons. Firstly, the MMR in Moulvibazaar is high and requires attention from the global health community. Secondly, Moulvibazaar has existing infrastructure which Maa can use, and key stakeholders are keen to help mothers in this region.

The biggest district hospital in Moulvibazaar is called Moulvibazaar Sadar Hospital and it has the resources to deal with Emergency Obstetric Cases (EmoC). These are usually complicated pregnancies which often require surgical interventions for safe delivery, such as caesarian sections. Other than this large health facility, there are smaller government-owned health facilities, however there is no information on the exact number of such facilities. What is known, however, is the total number of beds available for patients (not just pregnant women). Currently, 274 beds are available in the entire district with a population of 1.9 million people. There are an extra 407 beds available in 35 highly expensive private healthcare centres. Further, rural areas have a large shortage of doctors (discussed in Specialised doctors section) and this trend holds true for Moulvibazaar too. There are 102 doctors and 85 nurses available in government-owned hospitals and a further 109 doctors in private clinics. Evidently, there is a critical shortage of healthcare professionals in Moulvibazaar and Bangladesh in general.

In 2017, BRAC noted that there are 47 Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) operating in Moulvibazaar. Of these, there are two known NGOs working on improving maternal healthcare services; Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) and The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). BRAC has 31 Shasthy kormis (senior health workers) and 325 Shasthya shebikas (health worker) in Moulvibazaar (See Health Brigade Members section). UNFPA have also very recently initiated a programme to increase the number of midwives in Moulvibazaar (see Midwives section).

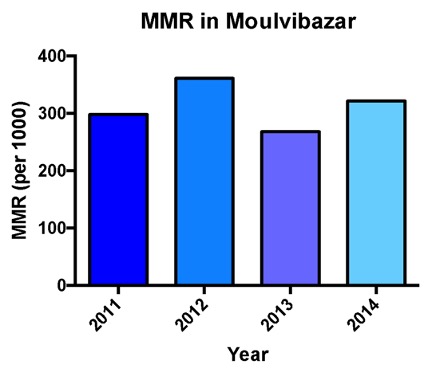

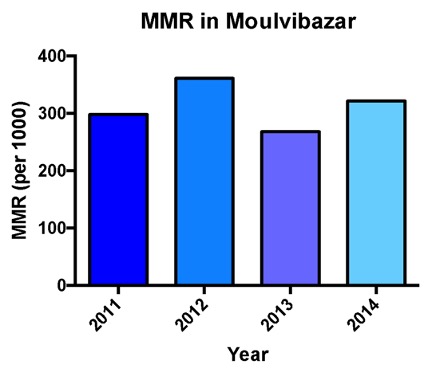

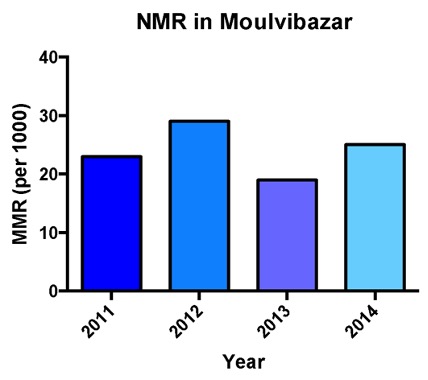

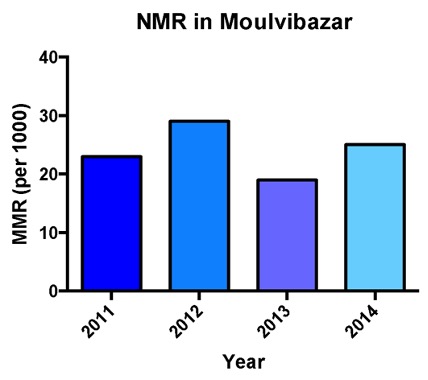

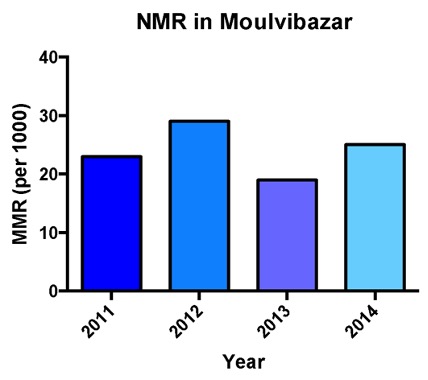

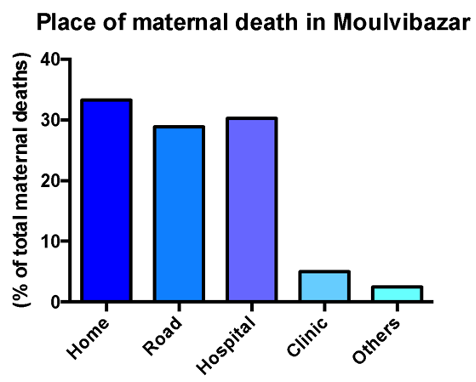

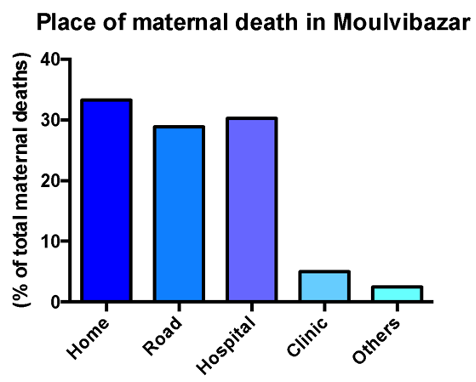

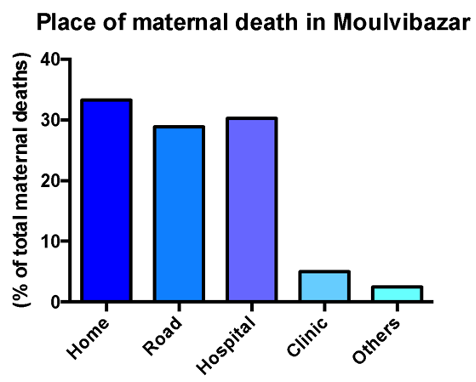

There is a lack of data and statistics on maternal health outcomes in Moulvibazaar. This is mainly due to the existence of a large population who are very hard to reach: the tea garden population. A new initiative, called the Maternal Death Surveillance Response (MDSR), was established in several Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), including Bangladesh. This is a tool to assist the collection of more comprehensive data on maternal mortality. Researchers went to Moulvibazaar to perform social and verbal autopsies. Figure 3 and 4 show that between 2011 and 2014, there were no significant changes in maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and neonatal mortality rate. This is in line with national figures, which show that MMR is stagnant in Bangladesh. However, these statistics do suggest that the MMR of Moulvibazaar is higher than the national average of 194 deaths per 100,000 live births. Interestingly, the MDSR report (2015) also explored the place of maternal death (Figure 5). A third of women died at home during birth, a third died on the way to a hospital and a third died in hospital. These locations of maternal death illustrate the barriers that exist for women to get good quality maternal healthcare. The 3-delay model explores this further.

Figure 3: Maternal mortality ratio in Moulvibazaar over a 4-year period. Adapted from MDSR (2015).

Figure 4: Neonatal mortality rates in Moulvibazaar over a 4-year period. Adapted from MDSR (2015).

Figure 5: Percentage of mothers dying in different locations. Adapted from MDSR (2015).

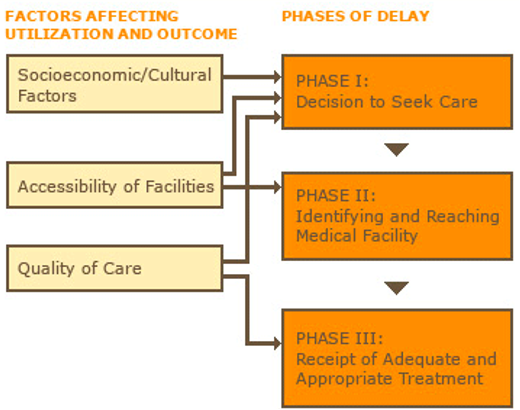

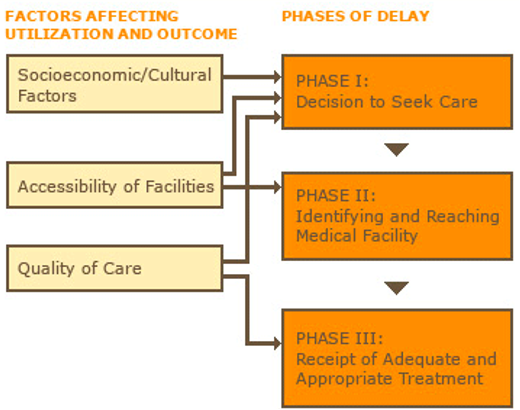

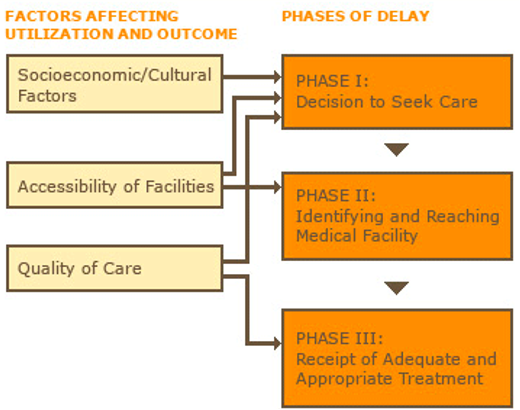

The 3-delay model provides a framework for understanding factors causing maternal mortality. It highlights the three main barriers that exist for mothers to get appropriate healthcare before and during delivery. Figure 6 illustrates this model.

The first stage of the ‘Three-Delay Model’ is a delay in decision-making to seek help. This is mainly due to the fact that pregnant women and family members are unable to decide if and when help is required to avoid maternal death. The following factors contribute to this delay:

To tackle this first barrier, the HS model has HBMs and WGs who will educate pregnant women on maternal health issues. Mothers will be informed about complications and when to seek help. ANCs will be carried out by HBMs at home to identify ‘red flag symptoms’ and those high-risk mothers will be referred to the Maa clinic, thus making the decision of seeking help faster.

The second stage of the ‘Three-Delay Model’ is a delay in reaching care. Factors that contribute to this include:

In order to tackle the delay in arranging transport, Maa will provide an innovative ambulance service to transfer patients. A traditional auto-rickshaw vehicle will be converted into a make-shift ambulance by building a flat surface within, which will act as a bed for the pregnant mother to lie down on.

The third stage of the ‘Three-Delay Model’ is a delay in receiving adequate healthcare. Factors contributing to this delay include:

In order to tackle the delay, Maa specialised doctors will refer mothers to a government hospital, which has the required infrastructure and resources to deal with EmoC. The HS model is a primary healthcare model which aims to provide rapid referral for mothers. During the referral process, Maa doctors will be able to provide the hospital with all relevant health data regarding each mother, by using the MaaConnect App.

Figure 6: The three-delay model.

Bangladesh is an example of a setting in which there are several barriers to providing good quality healthcare, including maternal healthcare. The major problem is that ‘too little, too late’ care is provided to most mothers. This is a complex issue. Firstly, many mothers are unable to access health facilities. Several reasons exist for this: long distance to facility; poor road infrastructure; unfavourable weather conditions and cultural barriers. If they can somehow access a hospital or clinic, the facilities and staff are often unable to offer vital care and treatment in a timely manner, due to systemic constraints such as lack of resources and overcrowded hospitals. An important intervention to reduce ‘too little, too late’ care is by providing mothers with ANCs in the local community and to provide follow up care in the intrapartum phase. Therefore, Maa will use these interventions in the Hub-spoke project.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2013). District statistics 2011 – Moulvibazaar. Reproduction, Documentation and Publication (RDP) Section, FA & MIS, BBS

Abdullah. A. M., and Halim. A., (2015). Maternal and perinatal death review. Reproductive and Child Health Unit, Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB)

Copyright Maternal Aid Association 2023. UK Registered Charity 1166021

Fill in your details and stay up to date with our latest news